Do it Now, Jump the Table

Finalist for the BBC Short Story Award, 2015

Standing on a petrol station forecourt in a pitch black valley in Wales, Thom remembered his girlfriend’s parents liked to walk around their house naked. Well, not exactly true. Sometimes they wore clothes. Susan had given him all the necessary details, such as how her mother, Lindy, would probably be wearing an elasticated tent dress with a floral print on it, that she kept hanging on a peg in the hall, in case someone she didn’t know knocked on the door. Likewise her father, Alistair, had his own peg next to hers where he hung an old pair of tennis shorts.

‘Modesty clothes,’ Susan had called them. ‘Anyway, most likely – they’ll be dressed when you turn up. So nothing to worry about.’

For Thom, most likely was plenty to worry about.

He pushed the nozzle of the pump into the tank and listened to the soothing gush of petrol. The car made ticking appreciative noises as the engine cooled. He smelt the cool night air, full of the scent of rock and fir trees and peaty soil, mingling with the smell of petrol, softly rising from the nozzle. He let his finger off the pump’s trigger, and stared beyond the acidic light of the forecourt into the velvet darkness of the Welsh night. He saw a bank of trees, dimly illuminated, and the beginning of a hillside, rising steeply.

The nudity wasn’t the problem, he thought. It was the other thing that Susan had gone on to mention:

‘What touching?’ he’d asked.

‘They might touch each other in a way that’s – inappropriate.’

‘How?’

‘I don’t know. A pat on the bum maybe.’ Susan had been hesitant. ‘You know – like when they’re passing each other on the stairs.’

‘Well – what can I say – it sounds sweet. Suse – I’m sure I’ll cope.’

‘Dad likes to cup her breast at the kitchen sink.’

‘Right.’ Thom had looked at Susan, wanting to laugh, wondering how serious he should be taking this and whether (a slight possibility) she was teasing. It was going to be the first time he met the parents.

‘Just – don’t make anything of it. Don’t react,’ she’d said.

‘Keep calm and don’t stare!’ he’d joked. She hadn’t replied. ‘We don’t choose our parents, do we?,’ he’d added, expecting her to agree. But instead she frowned, and he wondered whether she’d taken offence from an insult he hadn’t meant to give.

The farmhouse was old and large and not very well lit, as if this far up the valley electricity had dwindled to a trickle. He parked the car and knocked on the door, his bags in his hands, listening to a steady string of drips falling from a downpipe. Through a panel of pebbled glass he saw Susan approaching. She opened the door and threw her arms round him. ‘You got here,’ she whispered. ‘I can’t believe you got here.’

Behind her, he saw Susan’s mother take a step towards him from a back room, before she halted to let her daughter complete the hug. It was a gloomy corridor, lit by a single low energy bulb, and he couldn’t see her properly.

‘What have you eaten?’ Susan asked.

‘Crisps and chocolate. Then more crisps.’

‘Right – so we need to sort you out.’

Susan brought him into the hall and called out to her mother. When Lindy came forward, he saw she was wearing the thing that must be the elasticated tent dress. It did have a floral print on it. Her shoulders were bare and freckled and her knees and legs looked dirty. She gave him a welcoming kiss on his cheek, holding him tight with large fleshy arms, and as she let him go, gave him a slyly appraising wink.

‘Yep – he’ll do, Suse,’ she said.

‘Mum!’ Susan replied, giving an exaggerated roll of her eyes. ‘Just ignore my mother, will you?’ She turned to Lindy. ‘And you, behave.’ They had terrible fallouts, Susan had told him, but it seemed his arrival was a good time to show their love. Susan gave her mother a hug and, during an embrace that seemed to have several ritual stages of rubbing each other’s backs and stroking each other’s hair – Thom noticed the couple of pegs behind the door, where Lindy and Alistair’s modesty covers could be hung. Both pegs were empty.

They went into a large kitchen at the back of the house. It was a cluttered room with floor to ceiling shelves loaded with saucepans and cookbooks and a long Welsh dresser rammed with stacks of paper, magazines and crockery. In one corner of the room, hardly noticeable, was an apparently naked man sitting on a Lloyd Loom chair, filling in a crossword.

‘My father,’ Susan introduced.

‘Alistair,’ the man said. He stood up to shake Thom’s hand, and Thom couldn’t help but drop his gaze to see the man was wearing a pair of shorts.

‘Six across is a bugger,’ Alistair said, in a soft Welsh accent.

‘This man,’ Lindy said, ‘has never completed a crossword in his life.’ She stepped over to him and pinched his nose.

‘Ouch, that hurt it did,’ he laughed.

‘Meant to.’ She cleared a box of fruit from the table and served him a bowl of bright red soup. ‘Beetroot. Very delicious, but...’

‘...it gives you red pee,’ Alistair said.

‘Yes. So don’t worry.’

Susan sat next to him while he ate, mildly embarrassed while her parents continued to fuss, the father bringing him a glass of beer and the mother making him try some cheese she’d bought earlier that day. He noticed the glances the parents gave each other – little half-winks and occasional giggles. They’re flirting, he thought – they’re actually flirting with each other. ‘You’ll get used to them,’ Susan said, wearily. ‘These two are like a couple of teenagers.’ It was said, not entirely jokingly, Thom could tell that much, and Lindy seemed to take notice, raising her eyebrows at her daughter.

‘Alistair,’ Lindy said in a theatrical whisper, ‘let’s leave the young couple to it, shall we?’

Alistair screwed his face up in delight, and jogged towards the door, light on his feet. ‘Nice to meet you, Thom, we’ll have some time together tomorrow,’ he said. He trailed his fingers across his wife’s bum as he passed. ‘Right-o peaches,’ he said, as they left.

Susan put her head down on the table, in mock despair.

With the parental double-act gone, it was suddenly very quiet in the kitchen.

‘Did your dad just call her peaches?’ Thom asked.

‘Don’t,’ Susan replied.

After the soup they went up to Susan’s bedroom. The farmhouse seemed to be mostly unlit, with long dingy corridors and rooms filled with heavy furniture on thin carpets. In each corner Thom expected he might see the father, ready for a late night chat, or the mother wanting to give him a crushing hug again. He was relieved to get into the bedroom, where a stereo was playing and several sidelights were left on. Clearly a freer flow of electricity was allowed in there.

He took a shower in the en suite, glad to be back with his girlfriend. Glad, too, that the parents had clearly opted to wear clothes for the weekend. Naked parents was something he wouldn’t have to deal with, at least.

When he came out, Susan was already in bed. He switched the light off and got in beside her.

‘Susan’ he whispered, ‘do you think I passed the boyfriend test?’

‘You did very well.’

‘What’s that – a pass, a distinction?’

‘I think, a merit.’

‘Merit’s good, right?’

‘But now you’re being needy.’ She gave him a kiss on his forehead. Their code to let him know she wanted to sleep.

He lay back on his pillow, listening to the sound of sheep out on the hillsides, and of running water somewhere near the house. It was quiet. Thrillingly quiet. Susan began to breath deeply, and he locked his fingers into hers, thinking of the journey he’d done. He’d felt special at the petrol station. A traveller, paused. The lights of the forecourt had shone dimly off the curves of the car’s roof. His car had looked, briefly, like a plane does in a hangar, full of potential, designed to move between two very different worlds. The last few miles up the valley to the farmhouse at Blaen-y-cym had been narrow, and driving it had felt like following a river to its source – the road growing ever smaller until, eventually, it had been a single lane between dry stone walls. That Susan had been here, found at the river’s source seemed, as he fell asleep, to have great significance. He’d found her, in all the permutations of motorways and junctions and roads and lanes, like she’d hidden as far away as possible in an intricate puzzle.

He woke early in the bright cold bedroom, and placed the palm of his hand on the wall next to him. It felt damp and solid. Susan was warm, deeply asleep, and he noticed she was wearing a pair of man’s brushed cotton pyjamas he’d never seen before. Candy stripe. Perhaps they belonged to the father, Thom thought. He went to the window and looked outside at a vividly green Welsh valley. It was steeper and smaller than he’d imagined last night, with outcrops of dark grey rock and banks of fir trees above him. The sheep were well into their day already, dotted across the hillside, bleating to each other.

He looked back at Susan. She was lying on her back, with her mouth slightly open. When she was this fast asleep, her chin was slack and her neck looked thicker. She resembled her mother.

‘You awake?’ he whispered. She didn’t answer. This was his girlfriend, but she seemed different from the one who rushed her breakfast in their flat in South London, who travelled on a packed tube with him, until their routes separated at Oxford Circus, him going west and her going east on the Central Line, a quick peck on the cheek in the single chamber, deep underground, where the tube lines met. Different from the girlfriend he emailed from his desk, met at restaurants, chose their Friday night takeaway with. This girl in the bed was the Welsh version of the girl he knew, who wore woollen socks to sleep in, and was curiously quiet without the endless distractions and subjects that London threw at them.

Hearing the sounds of plates being washed up, and a kettle coming to the boil, he went downstairs. Lindy was at the kitchen sink, wearing the same elasticated tent dress from the night before. He noticed the print was of small sunflowers, with tiny bees buzzing round the petals.

She gave him a broad smile, but stopped short of a hug this time. ‘Will you have poached eggs?’ she asked.

‘Please.’

‘I’ll poach you a couple. And coffee, of course – you boys love your coffee, don’t you. Did you sleep well?’

He nodded. ‘Yes. Very.’

‘This valley has a magical air, Thom. Sleep comes easy here.’

While she made the eggs she told him about moving to the house, in the early-eighties, with Susan a grubby-faced babe in arms, allowed to crawl across the flagstones and out among the sheep. How Alistair had had plans to harness the water and wind power, even back then, except his mill and wind turbine had been a beautiful but endlessly collapsing project.

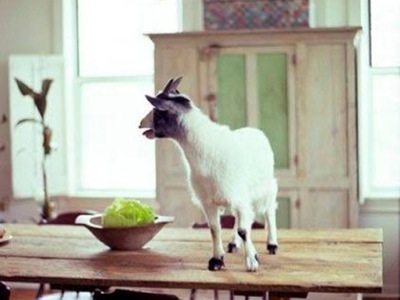

‘Sometimes a sheep would wander into the kitchen. It would come in here and get scared because it was in a house, so it would jump up on the table. And just stand there. Alistair – I’d go – a sheep’s just jumped the table!’ She sighed, in a moment of quiet contemplation. ‘Sometimes you’ve just got to jump the table, Thom.’ She held his gaze. ‘None of that happens now. Even the sheep have changed – why does – why does everything have to change?’

He wasn’t sure whether he was being asked a question.

‘Now – Sue’s told you we’re not keen on wearing clothes?’

‘Oh yeah - that – I’m fine about it.’

‘We can keep these things on if you’d rather? We don’t want you to feel embarrassed.’

‘Really, whatever’s most comfortable for you.’

She patted his arm, affectionately. ‘I like you. So, Thom, what you need to do now is go and see the veg patch – Alistair’s out there waiting to give the tour – it’s the love of his life. He’s very boring about it but you’ll humour him, won’t you?’

Thom smiled, liking this woman and her soft Welsh accent and her moments of private reverie. Thom heard the bath taps running upstairs, and guessed Susan was going to have a long morning soak in Welsh water, by way of anointment. She said it was her favourite thing to do here.

‘Belief, and love,’ Lindy said, cryptically. ‘Go and take a look.’

He wandered out with his coffee, across a patio, and into an extensive kitchen garden that spread up the hillside. Alistair seemed to be waiting for him by some rambling courgettes, wearing his pair of off-white tennis shorts. ‘Come to see my veggies, Thom?’ Alistair said in a sing song voice.

‘Lead the way.’

Alistair quickly explained how the veg patch was a miracle to have grown at all. ‘Acidic water, absolute absence of workable topsoil, rock shale peppering the ground,’ he listed. ‘And so cold this high up the mountain the spring’s a month late. When we came to Blaen,’ Alastair explained, stopping by some waist high fennel, ‘it was nothing but sheep dung and wiregrass out here.’ A gentle Welsh intonation came through in every other word. ‘The dung used to get between the toes,’ he added. ‘Had to flick the stuff off each time I went in the kitchen. So that was no good, no good at all. But then I thought to myself, I did, I thought – dung!’

‘Dung?’

‘Hundreds of years of it. My veggies love it. Can’t get enough.’ He pointed out his crops, proudly, with the tip of his trowel, ‘aubergines, peppers, leeks, potatoes, garlic, cabbages, cauliflowers. You see? Up there, Thom, you won’t believe but there’s espaliers of quince, plum and damsons. Never been grown in this valley, not to my knowledge.’ He looked thoroughly amazed at the things he was saying. ‘And hot Welsh chillies – who’d have thought it!’

Alistair’s tennis shorts were frayed and well worn, and it was clear he wasn’t wearing pants under them. The button above the fly was missing, and the shorts seemed to be held up by chance – perhaps by a single tooth of the zip.

‘But oh – the slugs – we do have a problem with slugs. Oh yes. They come down from the crags during the night, and feast themselves rotten.’

‘My dad drowns them in beer,’ Thom said.

‘Oh – really?’

Thom realised that to this man, all life was probably sacred. ‘You don’t kill them, do you.’

Alistair smiled gently and rubbed his chin. ‘No, not that. I negotiate with them. I persuade them to go different ways. The slug is a fellow of habit, you know, much like you and me. They like to follow their own trails – they get nervous striking out on new paths.’

‘Right.’

‘So if you wash their trails away, behind them like – you can coax them to slide off into the fields, little by little.’

‘That seems quite a lot of effort.’

‘But so much fun, too!’ Alistair replied, enthusiastically. ‘Lindy picks them up and takes them down the lane on her bike.’

Thom imagined the mother of his girlfriend riding naked on the old sit up and beg bike he’d seen by the front door, a bucket of slugs hanging from a handlebar.

‘Susan is very fond of you,’ Alistair said, out of the blue. ‘We grew her too in this valley. I don’t know how she manages in London, I really don’t.’

Thom nodded, not wanting to comment. Seeing Susan here, in this remote part of Wales, was explaining much of her behaviour: her bewilderment to be sitting on a packed London bus, her moments of dreamy withdrawal in noisy situations, the thick jumpers she wore in a flat that was never going to have the coldness of this draughty farmhouse, the desire to walk, always. Seeing this Welsh quietness, the soft green light that fell on the hillsides, the damp stoney smell of the air, Susan clearly found the rest of the world a compromised place.

‘She hasn’t always made the right choices,’ Alistair added, somewhat mischievously. ‘Not with men.’ He bent down to tend the vegetables, scratching the soil with his trowel.

Whatever held those shorts up, it was a tension Thom felt very aware of. Surely a bend in the wrong direction, or pulling too hard at a weed, and those shorts would spring open. Nakedness was one thing, but sudden nakedness, surely, another. The missing button, the teeth on the old zip about to slip – it seemed Alistair’s clothes were itching to come off.

Sure enough, later in the day the shorts were gone. From an upstairs window Thom looked down on Alistair, now completely naked, as he wheeled a barrow up the brick path between the vegetables. Thom was struck by the skinniness of the man’s legs, compared to the tight paunch of his belly, his bony barrelled chest and his sloping shoulders, all that skin pink-raw in the cold lunchtime shadow behind the house. And he was strangely hairy in places. For example, above his bum, on either side of his spine, the goat-like beginnings of a satyr’s tail.

‘Your dad’s not wearing any clothes,’ he said to Susan, dryly.

‘So he approves of you,’ she replied, unconcerned.

‘Really? So if he likes your boyfriends he takes his clothes off?’

‘That’s about it.’

Through the window, Alistair began to fork manure over a row of onions. His balls swung freely between his legs. Oh dear, Thom muttered, to himself. The only clothing Alistair wore was a pair of lace-less trainers. It made him look like a cricket pitch streaker.

Thom considered whether Lindy, somewhere in the house, had also removed her clothes. He imagined her lurking in the darkened hallway, wriggling out of that loose dress like she was doing a hula hoop, then hanging it on the peg next to her husband’s shorts.

‘What about your mum?’ he asked. ‘Will she be stripped off by now?’

Susan didn’t reply. He turned to see her giving him a weary heard-it-all before look.

‘Dad usually takes his lead from her.’

‘OK. So that elasticated dress will already be hung up?’

‘Don’t get silly about it,’ she said, and he realised she’d probably had this same conversation with all her previous boyfriends. They’d all said the wrong thing in their own way, and they’d all not lasted.

‘I’m teasing,’ he said.

‘Good. I’m going to have a bath.’

‘Another one?’

‘It’s what I do here.’

While she ran the bath, Thom studied the naked man in the garden. Alistair was pulling up vegetables, carefully, diligently, with a curious look of – not quite sadness – but concern, as if he was doing a great wrong. At times, he had to straddle the rows, squatting as he tugged the carrots from the ground, the soil-dirty leaves suddenly springing free and slapping him in the groin.

Thom decided to go downstairs and join him, determined to act more maturely, more casually, than the list of Susan’s failed boyfriends. The whole weekend had the aspect of a test. A meet the parents test. He would pass with flying colours.

In the kitchen there was a homely smell of baking coming from the Aga, but no sign of anyone. He tasted some leftover dough from the side of a mixing bowl. Scone mix, he thought, or some sort of Welsh cake. He went outside.

‘Hi, Alistair,’ he called.

‘Hello!’ Alistair replied, cheerily, holding up a bunch of carrots in his hand, like a prize. It was an absurd sight, really, a naked man holding aloft a bunch of dirty carrots.

‘They look great.’

‘We’ll have them tonight.’ Thom couldn’t help noticing the older man’s balls retracting, as Alistair laughed. ‘Suse in the bath?’

‘Yes.’

‘She likes a bath.’ Alistair bent to the vegetables again, and Thom sat down. Good, that went OK, he thought. It was a proving of sorts, to have had this conversation, however simple. He’d been able to talk, man to naked man, and not be embarrassed about it. He took out a book and began to read, and easily read six or seven sentences before realising he hadn’t taken a single word in. Someone was in the kitchen: the Aga’s heavy door was being opened. Bowls were being put in the sink. He turned a page, realising he’d been on the same one just a bit too long.

Lindy walked out onto the patio, totally naked, carrying a tray of fresh baked scones. The scones, it appeared, might have been a subtle way of concealing herself, distracting him. But for Thom the tray of scones made it worse. This woman, the mother of his girlfriend, her nudity and the fresh warm scones seemed to be a combined offer.

‘I’ve been busy,’ she said. She put the tray down on the patio table and stood before him.

Resolutely, heroically, he looked her in the eye.

‘Good,’ she said. ‘So – what will you have?’

Altogether, what needed to be accepted and what needed to be declined seemed catastrophically mingled. At the edge of his vision, her large weighty breasts looked back at him. Two sad unblinking eyes.

‘They – they all look delicious, Mrs Maddox.’

‘Oh, please, it’s Lindy,’ she said. ‘Susan!’ she called, to the open window above them: ‘Scones.’

‘She’s having a bath,’ he said.

‘Again? That girl!’ Lindy started to walk back to the kitchen, the crease beneath her wide dimpled arse making a splendid smile for him and for him alone.

This was a bizarre moment, Thom considered, congratulating himself that he hadn’t giggled or blushed or done anything immature. But it was still bizarre. The parents had just taken their clothes off. And no one was mentioning it.

From the kitchen he began to hear Lindy singing a little made up song. He couldn’t make out all the words, but it seemed to be about the wind turbine that Alistair had tried, and failed, to make. Prompted by their talk, earlier. Then a second verse about some sort of home-made garden shower. It was a charming song.

‘We have ravens here,’ Lindy said when she returned, carrying small ceramic pots of jam and cream. ‘They circle above the crags and drop stones on the rabbits. They’re very clever birds and have a tremendous aim.’

He looked up at the crags, wishing briefly that he was up there, a free and uncomplicated space.

‘Now,’ Lindy said, cutting open one of the scones. ‘Are you a jam on top or a cream on top man?’

He’d finished a second scone before Susan came out. She walked languidly across the patio, kissed him on the cheek, and lay a hand on his shoulder. Susan was taller in Wales. Her joints relaxed.

‘You all getting on?’ she said, good humoured.

Her mother beamed at her. ‘He’s sweet, Sue. Where did you find this lovely man?’

Susan kissed him again, sealing the general approval. She reached for a scone. ‘I thought I could take the car, Mum, and show him Crickhowell. Would you mind?’

‘What’s in Crickhowell?’ he asked.

‘Nothing, but it’s not here and I’m sure you need a break from my parents.’

‘There’s a farmer’s market,’ Lindy said.

‘Right. There you go. There’s a farmer’s market.’ Susan ate the scone, holding her hand under it to catch the crumbs. Thom noticed her wrist resembled her mother’s. Thicker than it should be. It was another of several similarities between these two women he’d noticed. The way they sat, for example, with the right foot placed neatly in front of the left. A slight lumpiness to the knees, as if they shared an extra bone there. Lindy looked back at him, trying to guess his thoughts. Sitting here, he realised, was a naked version of his girlfriend, given thirty years.

In Crickhowell they found an impressive cheese stall in the corner of the square that stood for the farmer’s market, but every other shop in the town seemed to be Poundland, or a version of it. They walked up the high street, turned, and walked down it again.

‘Pub?’ he suggested.

‘Thought you’d never ask.’

They found a pub and sat at the window. He had a pint of some locally brewed beer, and she decided to have a cappuccino from a machine they had to switch on for her.

‘Well, here we are. Here’s my home,’ she said.

‘Cheers,’ he replied, raising his drink. Through the window he looked up the high street. It had started to drizzle and the few people out there – who were mostly old – seemed to bend into the weather. They looked grim faced. Crickhowell looked a grumpy sort of place. Having spent the morning with a couple of naturists – who radiated a sense of enthusiasm – it suddenly appeared that it might be the drab coloured fleeces, the shapeless anoraks, the ill-fitting jeans, that might be making these people in Crickhowell so heavy and depressed. He compared them to the nimble way Alistair tip toed through the veg patch, or Lindy’s easy jolly swagger as she carried the scones.

‘I’m having odd thoughts,’ he said.

She laughed. ‘How are you finding it at Blaen-y-cym? Is it OK?’

‘Fine.’

‘And the general nudiness?’

‘Totally cool. It didn’t really occur to me,’ he lied.

She sipped her coffee. They had these silences, often, like he was expected to keep the conversations going. She looked through the window.

‘What about you?’ he asked. ‘How’s it being at home?’

She shrugged, non-committal. ‘Mum and Dad wind me up – you know that.’

He nodded, half-remembering old conversations, but not quite getting what her angle had been.

‘It’s all the lovey-dovey stuff,’ she explained. ‘It’s cringing.’ She described how her father left snowdrops or bluebells at her mum’s breakfast placemat, without fail, after the walks he took at dawn. Later in the year it would be dandelions, an owl’s pellet, lichen, even moss. He’d lay them out for her, making a gift out of something he found simply beautiful.

‘He does that?’

‘Every day.’

Thom suspected a comparison might be being made. Him, rushed each morning, standing up to eat his toast, no time for wandering around hills filling his pockets with trinkets, thinking of beauty. He decided to draw attention to it:

‘I’m sorry, for not doing that.’

‘Doing what?’

‘Leaving you little daily gifts.’

‘We have jobs, Thom.’

‘Still.’

‘If you did that for me – I’d find it weird. No one does that, at our age.’

‘It’s sweet. Isn’t it?’

She clearly didn’t think so. ‘The way they behave – it’s like the honeymoon never wore off.’

‘So what about your mum – what does she do for him?’

She smiled, despite herself. ‘Mum makes vegetable sculptures for the dinner table – she does these little comic still lives with them – you know – aubergine men with carrot legs and mushroom caps, stuck together with cocktail sticks, playing courgette saxophones. There was this entire Mardi Gras band, once. It was amazing.’

‘Wow.’

‘She sings, too.’

‘Yeah – I heard one this morning. About one of your father’s inventions.’

‘The one about the wind turbine?’

‘Yeah. For what it’s worth – I think your parents are great,’ he said. ‘You know – it’s clear they’re still really in love.’ He’d been struck by it, the abundance of affection they had for each other, mentally comparing them to his own parents, who were always scoring points in petty arguments against one another. A thirty year war with no achievable goals, no conceivable end.

‘Don’t be fooled by it – it’s not always like that,’ she said. ‘They can get pretty bitter.’

Like us, he thought. No. Bitterness wasn’t the issue – it was a general distance he felt. Somehow they never became close enough, they never stopped and just held each other. They were always too busy. All they needed to do was appreciate what they had and be more meaningful with their time. Let the world turn without them.

Back at Blaen-y-cym, in the early evening light, he climbed up to the crags behind the house. The sheep eyed him suspiciously as he passed, standing a few feet away and making little stumbling runs to keep their distance. They seemed so nervous, he couldn’t believe any one of them had ever walked into the farmhouse kitchen and jumped on the table. Maybe Lindy had been joking, or making some kind of point he couldn’t work out. When he stopped he listened to the sound of the sheep chewing, and the noises from the valley rising up at him. Streams, running through the bracken, somewhere along the hill. There were bones among the rocks, lots of them. Perhaps they were from rabbits, where the ravens had pelted them.

Blaen-y-cym looked peaceful. A peaceful place to grow up in, and to grow old in, but a place Susan couldn’t wait to get away from after a few days, or so she claimed. She was having yet another bath. That was the third of the day. In London, she showered, but in Wales she seemed to spend as much time as possible soaking. The gentle Welsh water, she explained, opened her pores and softened her bones. As if she was porous here, whereas in London the hard water ran straight off, never quite cleansing her.

He watched Lindy and Alistair come out of a side door, carrying what seemed like a single divan bed. They were doing up the spare room, so it made sense. Both of them were naked, and they carried the bed to one of the sheds, where there was some other furniture waiting to be recycled. They walked gingerly, both in their laceless trainers, making little adjustments with their grip. It looked like a scene in a comedy sketch: a couple of randy lovers, caught mid-act, having to carry their bed around.

Back at the farmhouse, he walked into the en-suite to find Susan was still in the bath. She lay perfectly still while he sat on a stool next to her. He dipped the ends of his fingers in the water.

‘Hello, you,’ she said. ‘How was the climb?’

‘Lovely. You come from a beautiful place.’

He pictured their life in London, constantly fuelled by their jobs, their social lives, their endless day-to-day struggle to convince themselves they were going in the right direction. They never stopped. Here, they were in the stillness of her family home, a farmhouse in a valley that hardly stirred, it had exposed a silence they didn’t know quite how to fill.

He thought about getting in with her, but knew she didn’t like sharing baths. Bathing was a special thing for her, and sharing was somehow smutty, a transgression, even if it wasn’t. Plus the bath was quite narrow. They’d have to negotiate with their legs and it just wouldn’t work. Not with her.

He smiled, looking at her knees again. He’d never particularly noticed them in London, but here, half submerged, reminding him of her mother, they seemed peculiar.

‘What are you looking at?’

‘Your knees.’

She dipped them in the water and then let them rise again. He watched the water drying on her skin.

‘Have you seen Mum and Dad?’ she asked.

‘They’re carrying a bed round the garden.’

‘Really?’

He thought about telling her what a strange sight it had been, the two of them, naked, carrying the bed, but felt unsure how critical she allowed him to be when he talked about her parents. There were mixed signals. She found them maddening, had regular spats with her mother in particular, but then there’d been that extended hug in the entrance hall. A complex loyalty.

‘So – have you never been tempted – to join in with the naturist stuff?’ he asked.

‘No.’ She sounded perplexed, as if he was a million miles away from understanding this thing. ‘There’ve been occasions, Thom. Some of my school friends did it.’

‘What – with your parents?’

‘Yeah.’

‘What happened?’

‘I’m getting out, Thom, it’s getting cold.’

Dinner was an oddly formal affair. They sat in a chilly room around a long dark table and ate off fine china plates with silver cutlery. Lindy wore her elasticated tent-dress. Clearly there was a more complicated set of rules about nudity that Thom didn’t quite understand. Perhaps dressing for dinner was something even a naturist couldn’t give up on. In the centre of the table were two of Lindy’s vegetable sculptures: a couple of standard poodles, one made of cauliflower florets, and the other made from broccoli. The starter was purple kale, dressed with lemon and thyme. After that, they ate new potatoes with butter and chives, leeks, and some of those dark red carrots, washed and steamed and served whole. It was difficult to avoid the image of Alistair squatting over the carrot bed, tugging at the plants while his genitals shook and brushed the leaves. They drank a syrupy and deceptively strong parsnip wine, and by the time dessert was served, Thom felt unable to trust his judgement. He looked at his plate of steamed rhubarb with honey and oatmeal, wondering whether it was the wine that was making him feel at a remove from what was going on in the dining room, as if he was watching himself act in a play. The cauliflower poodle stared at him, eerily.

When Lindy went to fetch cream from the kitchen, a piece of her dress became wedged between her bum cheeks. It looked, momentarily, like her bum was trying to take a bite from the material and, for the first time, Thom wondered whether he preferred his girlfriend’s mother without her clothes on. Naked, she could be seen at face value, but with the silly dress on, there was an issue of poor concealment that drew attention to her body. The dress made her more naked, he thought.

He decided to down his wine, thinking a level of drunkenness was probably the best approach.

After the meal, they retired to the snug – a red walled room with three sofas in it and a woodburner set into a large hearth. Thom sat next to Susan, feeling the meal had been a success and that Susan must be thinking along similar lines by the way she curled herself into him. Just the night to go, and tomorrow they’d be setting off in the car, returning to London. He’d be back on home turf.

Lindy came in, bringing candles from the dining table to put on the mantelpiece and, standing on the rug in the centre of the room, she wriggled out of her tent-dress. She let it drop onto the floor and then she kicked it onto the chair with a toe.

Alistair followed suit. He slipped his tennis shorts off and folded them onto the armrest of the sofa, letting out a satisfied sigh as he did so. Susan didn’t seem to notice the parental striptease. Again, Thom had the sense that this moment was another of the pre-arranged tests in some kind of Maddox-family challenge; one he could easily fail. He chose to meet it head on, to show his lack of fear:

‘I think it’s great – being like you are,’ he said, trying not to sound like he was calling them freaks. ‘I mean the naturism.’

‘You do?’ Lindy said, obviously pleased.

‘Sure. It’s brilliant.’ He noticed the wine had affected his voice. He made a mental note to speak carefully.

‘We used to wear clothes before Suse was born,’ Lindy said. ‘All through the seventies – when everyone else was taking off their clothes – we were...’

‘...buttoned up,’ Alistair said, with a wink.

‘Yes. Buttoned up. Looking back – I don’t really understand it. Do you, love? Why were we so stiff back then?’

Alistair shrugged, happily. ‘I think it takes time in a marriage, until you’re so familiar with the other person that you hardly notice whether they’re wearing clothes or not. I mean – I really can’t tell, nowadays.’

‘And it saves a lot of money,’ Lindy said, with a conspiratorial whisper, ‘not to be following the fashions.’

‘Like you ever did, Mum,’ Susan said.

‘In my time, darling, I was able to turn a head or two.’

‘So who went first?’ Thom asked. ‘I mean – was it something you both agreed on, or what?’ Susan gave him a little warning glance, as if to say there’s more to my parents than their nudity. Change the subject.

‘Me,’ Alistair said, his eyes sparkling in the candlelight. ‘Soon after Suse came along in fact. I saw this beautiful baby – and you were, Susan, you were a wonder – and you’re there – this perfect little warm-skinned baby, and I said to myself Alistair, how did you get to be so far away from that?’

‘He said he was going to take his clothes off for an entire week,’ Lindy continued, affectionately, ‘and I told him – you do that for a whole week and then I’ll join you.’

Susan tapped Thom on his arm: ‘You do realise I’ve heard this story a thousand times.’

Thom looked at Susan’s parents as they smiled in the candlelight. It wasn’t their nudity that bothered him. It was how at ease they were. It was rare to meet two people so devoted, who seemed to wake up each day so full of love and contentment. It was as if the Welsh mountain air breathed a spell on them, each night. Perhaps this valley really was a magical place. A place of healing. Their two hearts beating as one, and a daily goal to do nothing but appreciate each other. Maybe it was the clothes, after all, that might be keeping him and Susan apart? Maybe putting on clothes made them look and act like other people. Made them disguised.

He felt he needed to tell Alistair and Lindy that in just twenty four hours their relationship had made a profound impact on him. Alistair smiled at him, as if reading his thoughts. Thom felt such warmth in there, in the snug, with the red walls and the feel of the parsnip wine in him.

‘I must admit,’ he began, ‘before I came here I was a little nervous – I’m from – you know, a fairly conventional background. But you’ve really opened my eyes to all this.

‘That’s good, Thom,’ Alistair said, ‘that’s good to hear.

‘In fact –‘ he stopped himself, enjoying the sense of a decision, carefully poised. ‘Actually – would it be crazy, I mean – you’ve got to say if it is – but how crazy would it be if I took my clothes off?’

Lindy laughed. ‘What, now?’

‘Yeah.’

‘Too much wine, methinks?’ Susan said, visibly tight-lipped.

‘No – no – come on,’ Thom said. ‘I’m serious.’

Susan went stern. ‘Why would you do that, Thom?’ she asked, somewhere between a smile and something else that wasn’t quite formed.

Thom looked back at her, wondering why she was being so brittle about this. He realised there was a problem here, a problem between them two – where there was this kind of repressed thinking. It had grown up in all sorts of areas between them. Not spending enough time on each other, not laughing enough. Not having as much fun as they should, because somehow over the months, their default state was to self-police against spontaneity. They were trying to act out some kind of couple he knew he didn’t – deep down – belong in. They were making this constant show to be mature and grown up and in fact they were just – boring.

‘Right,’ he said, feeling angry about all sorts of slights he’d built up. All sorts of vague resentments about the couple they’d become. He unbuttoned his shirt and took it off.

‘You’re going to drop your trousers now, aren’t you, Thom,’ Susan said, sounding like a bossy teacher. Some of my school friends used to do it, she’d actually said that, up in the bedroom. They’d taken their clothes off to join in with the parents. So why was it all OK then and not OK now? Perhaps, he wanted to tell her, perhaps if you and I were a little more free-spirited like your parents, then perhaps we’d get along better.

He had his hand on his belt. The decision already made. He was beyond the point of going back. Taking his trousers and pants off was just a formality now. He stood, unbuttoned his jeans, and pulled them and his boxers down, in one go.

Quickly. Disastrously. Even before he’d stepped out of his jeans he knew what a terrible mistake this was. He stood, exposing himself, looking down at his terrified penis and the sight of his cast off pants.

‘Well done, lad,’ Alistair said, in a room that suddenly felt incredibly silent. ‘How do you feel?’

‘Good,’ Thom said, lying. He felt appalled.

He glanced at Lindy, nervously, wanting an ally at least, and saw that she was openly checking him out. Unashamedly, she was appraising his groin. He sat down on the sofa as quick as he could. How dare she, he thought. All day long he’d assiduously not looked at her, and yet here she was, a seasoned pro, been doing it for years, and eyeing him up like a teenager.

‘I can’t believe you’ve just done that,’ Susan said, quietly, shielding her face with a hand. She was trying to sound amused, that this twist in the evening might yet be made into a joke, but he knew from the tone of her voice there were so many other layers to it, so many other things she was going to say. On the phone to a friend – So he stood there, right in front of Mum and Dad, and pulled his pants off. It just couldn’t be said in any other way. Or to him – You showed absolutely no respect for them, did you?

The atmosphere in the room had entirely changed. He lay his hands on his lap, a desperate concealment, attempting to talk about tomorrow, what they might do before the journey back, but it seemed ridiculous now. Everything he said was ridiculous.

He stared at the pathetic pile of his clothes where they lay on the rug, wishing his boxers weren’t left so openly displayed.

Lindy spoke quietly and deliberately: ‘You’re nicely built, Thom.’

‘Mum!’ Susan said, harshly.

‘I do a lot of running,’ Thom said, hearing his voice as if it was coming from another room. Running was something he’d like to be doing, right now, as fast as he could.

Lindy continued, addressing her husband. ‘You could do with a little more exercise yourself, Alistair.’

‘I’m quite happy the shape I am, love.’

But Lindy hadn’t quite finished. She looked at her husband with a sense of sadness, that there was an element of long-standing disappointment between them.

‘You’ve let yourself go – on the tummy, for one.’

Alistair stood. He proudly smacked his belly. ‘That,’ he said, ‘is the shape of a man who is content.’

Lindy raised her eyebrows, as if there was more to be said.

‘Anyway – ’ Alistair started, with a slightly ugly sneer. Thom could see the man was highly vexed. ‘Anyway – what about you...’ he gestured towards his wife, at her wide thighs filling the armchair, her belly hanging in a sad bow over the wisps of pubic hair. With a wave of his hand he drew attention to it, to a general sense of disgust.

‘Mum, Dad!’ Susan said. ‘Don’t.’

Alistair stood angrily, holding back the words he knew he could say. Instead, his chest blushed pink, and his cock pointed like a crooked finger towards his wife, accusing her. Lindy got up and stormed out of the room.

Alone with Susan in her bedroom, she was so furious, so full of all the things she was trying to formulate, that she actually said nothing. Eventually, lying stiffly in bed next to him, with the light off, she managed: ‘I can’t believe you did that.’

Here goes, Thom thought.

‘Have you got nothing to say?’

‘I thought it was the thing to do - I thought you said your school friends used to do it?’

‘Once. For a stupid dare. It was embarrassing then – and now...‘ She didn’t finish the sentence.

Thom realised this was probably the beginning of a whole series of talks they might have, possibly the beginning of an end for them, too. He’d made a fool of himself. He’d made a spectacle. But hadn’t his intentions been good ones – hadn’t he been so full of admiration for the parents’ abundance of love for each other that he wanted to try and discover it with Susan? Unfortunately, exposing himself had exposed them both, and their limitations.

Unable to sleep, and suspecting Susan was lying there, fuming, waiting for an argument neither of them wanted, he got out of bed and wandered through the unlit farmhouse.

In the dining room, both the vegetable poodles had lost their heads. He stood for a while in the snug, trying to replay the exact sequence of events. The parental striptease, his rash decision to join in, Lindy’s libidinous look, and Alistair’s reaction. Whichever way he viewed it, it looked bad. With a sigh he went through the darkened kitchen and out onto the patio. He walked up through the veg patch, where he noticed several huge slugs, very black, very long, were sliding towards the courgettes. Behind the outbuilding he found the bed the parents had brought out. The mattress was damp with dew, but he sat on it regardless. There were sheep around him, low down on the hillside. He watched a couple of them cautiously crossing the patio, and one, nervously step into the kitchen where he’d left the door open. He looked up to Susan’s window, wondering what the morning would bring him, and whether he would ever come to this place again. The source of the river, he thought, abstractly.

From inside the kitchen, he heard the sheep, jumping onto the table.

Do it now, Jump the Table